|

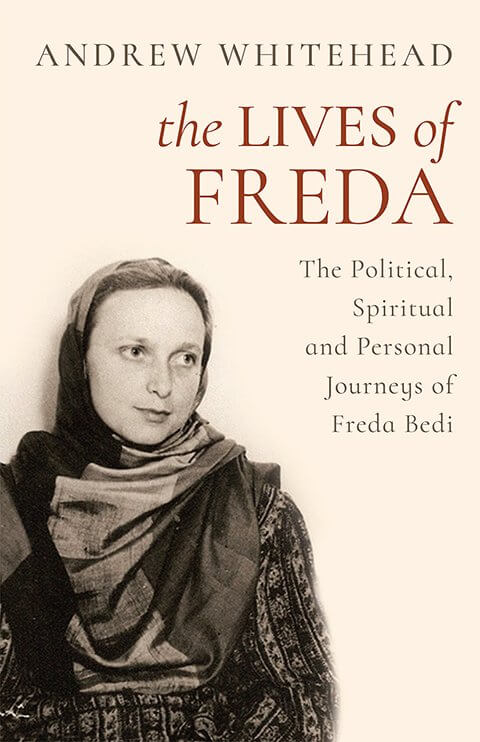

Here's Freda Bedi in her own voice. In the mid-1970s, while visiting her son Ranga in Calcutta, Freda - by then Sister Palmo - sat down with a cassette recorder and told the story of the first three decades or so of her life. This is a two minute extract from those tapes, describing how she first met her husband-to-be B.P.L. Bedi more than forty years earlier, when they were both students at Oxford. There's no trace here of a regional accent - indeed, if anything Freda has an 'Oxford' or establishment accent. She wouldn't have grown up speaking in this manner, so I imagine that at Oxford - as with so many northern students at this time - she tutored herself our of her East Midlands lilt. It is wonderful to be able to hear her voice - it's such an insight into character. And even though this is a brief extract, with the sound quality touched up to make it more clearly audible, you do get a sense of Freda's personality.

0 Comments

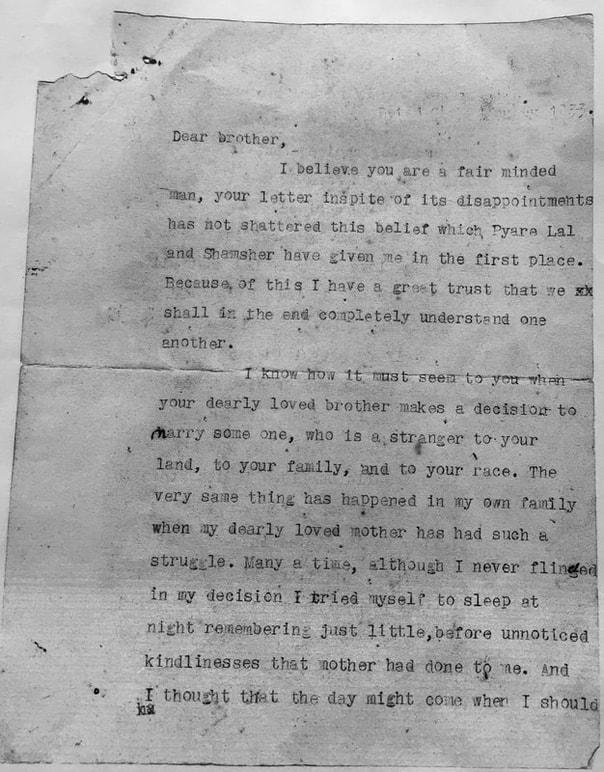

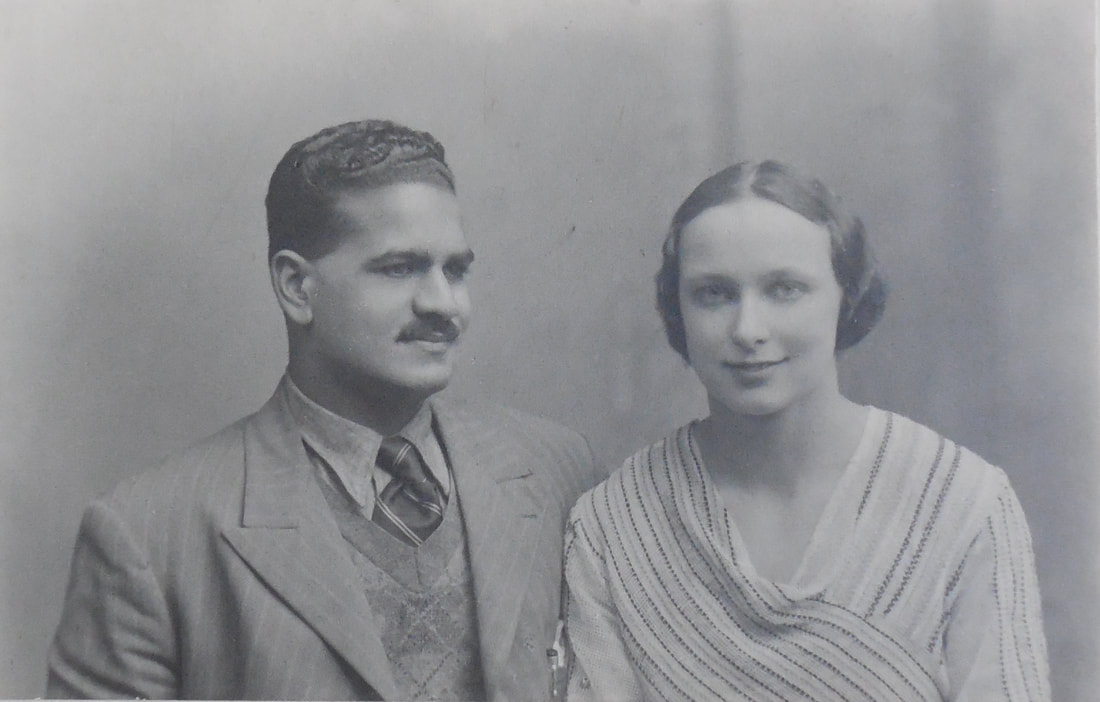

This truly remarkable letter written by Freda Bedi (she was then Freda Houlston) to her Punjabi boyfriend's brother has just come to light. It was almost certainly written early in 1933, just before Freda and B.P.L. Bedi got engaged. It's a touch frustrating to come across this after my biography The Lives of Freda has been published - but I'm so excited to have seen it. It is a deeply moving piece of writing! This is how I came across the letter. Earlier this month I met for the first time in Chennai B.P.L. Bedi's nephew, Inder, and his wife Meena. Inder's father, T.D. Bedi, was B.P.L. older brother and an ICS officer and magistrate - B.P.L's father died young so his older brother was the head of the family. Meena mentioned that when she was clearing out the family's Delhi house some years ago, she came across a letter Freda had written. It is posted here with Inder and Meena's kind permission. The letter is clearly in response to one that B.P.L. had written to his brother. B.P.L. shared his intention to marry his English girlfriend; T.D. seems to have replied saying - forget it, that's not what we sent you to Oxford for! It's curious that the letter is typed, undated and unsigned. I suspect that Freda wrote by hand and then a copy was typed out at T.D.'s request either to make it easier to read or more probably to share the letter within the Bedi family. There are some errors of spelling and grammar which Freda would not have made. In the text of the letter below, I have sought to reconstruct what Freda would originally have written - do bear in mind she was just twenty-one at the time: Dear brother, I believe you are a fair minded man, your letter in spite of its disappointments has not shattered this belief which Pyare Lal [B.P.L. Bedi] and Shamsher [Bahadur] have given me in the first place. Because of this I have a great trust that we shall in the end completely understand one another. I know how it must seem to you when your dearly loved brother makes a decision to marry some one who is a stranger to your land, to your family, and to your race. The very same thing has happened in my own family when my dearly loved mother has had such a struggle. Many a time, although I never flinched in my decision, I cried myself to sleep at night remembering just little, before unnoticed, kindnesses that mother had done for me. And I thought that the day might come when I should 2 have to make a choice between her and all my home associations and Pyare and a country which I loved but had never yet seen. God has spared me that heart breaking choice – but if it had to come, it would have been for the man I love and India that I should have decided. I don’t want to labour my sacrifice because I am so rich in the love of Pyare Lal that all else seems insignificant. By love I mean all the glory of the tender, strong, passionate, peace -ful, contended, self forgetful love of woman for man. I do not believe man was created to live without woman. As you love your brother, Bawa Sahib, so I love your brother. But you are man and I am woman, and while our love in its strength must be the same at the core, for me there is also another complexion to it. I see in Pyare Lal the father of my children, and I tremble to the passion of tenderness when I think I shall one day suckle his son at my breast. None but the finest children could be born of the spirit which unites us and 3 the strength of our bodies. I can never be an Indian woman and can not give him pure new children. Would that alone prejudice you against them? Piyare and I are one country in spirit and colour is unimportant beside that. When I loved Piyare first it was not for the first time, we came together out of space – we have loved before – and after this life we shall love again. I would account it an unbearable shame to weaken my love; it does not weaken, it strengthens. I was not brought up in an easy school. I do not ask ease from the future. I want to serve and to serve as best a woman can, by the side of her husband and children. I repeat – there is one thing I can not do; become an actual Indian woman. And I know full well that some woman of his own race will miss a perfect husband in Piyare. But my spirit is with India and not with 4 England, with Pyare and not with a man of my own country. My children will be an even greater bond. My clothes another. Would you deny me your perfect understanding for something I can not help? It just happened that I was born in England – but it also happened that my soul is not in this country but in another. I have a different mission from Miss Slade. [Madeleine Slade - a British woman who worked with Gandhi] India accepted her service, I hope and believe that she will accept mine. I should be the last person to hold Pyare back from completing the promise of the struggle of his early life. I would rather cut my throat than “demanise him”. This letter is equally addressed to Bhaboo Ji [B.P.L.'s mother]. Your sister, Sd. / Freda.

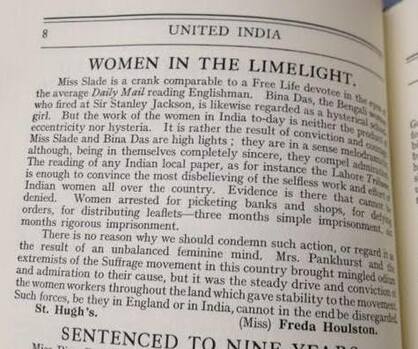

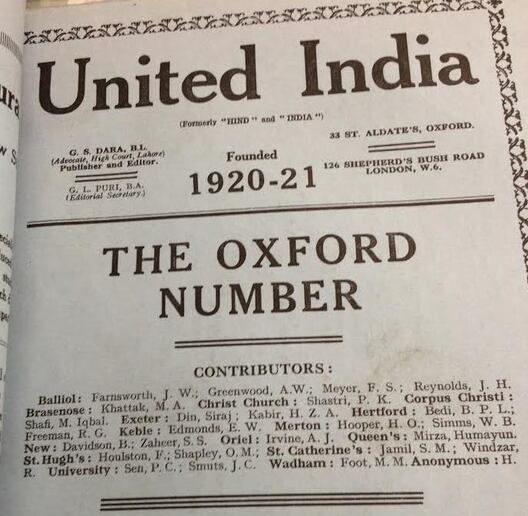

This was the journal in which Freda Bedi's (her maiden name was Houlston) first published writing about India appeared. United India was a curious, nationalist-minded, vaguely left-wing, journal published by an oddball in the Indian diaspora in the UK, G.S. Dara. Partly as a marketing ploy, I suspect, the issue for March 1932 was dubbed 'the Oxford number' and consisted of very short articles by more than twenty Oxford students. In June he followed up with a 'Cambridge number' of the journal. Along with Freda, one of her close friends, Olive Shapley contributed. Among Indian students, Freda's husband-to-be B.P.L. Bedi wrote for the special number, as did Sajjad Zaheer and Humayun Kabir. Michael Foot and Tony Greenwood later rose to prominence in Labour governments; Frank Meyer and Dick Freeman were at this time the leading student communists at Oxford.  Freda's own contribution was insubstantial - but shows a focus on women, an element of sympathy for Bina Das, a nationalist would-be assassin, and familiarity with the Tribune, the main nationalist daily in Lahore. Olive Shapley wrote a much more militant piece - let's remember this was still the Class-against-Class period of international communism which concludes:

If the woman's movement in India is to be used to prop up the capitalist system for a few more years before its inevitable collapse, then purdah and child-marriage would be lesser evils. The women of Russia did not achieve their emancipation through the media of welfare centres, baby clinics, and women's institutes, and it is greatly to be hoped that the women of India will not be deceived by these sops to their awakening consciousness. |

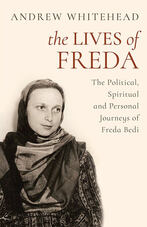

The Lives of Freda- a blog about my biography of Freda Bedi Archives

September 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed